The war also opened doors for African-Americans. And male engineers, once freed from laborious math work, could focus on more “serious” conceptual and analytical projects. A “girl” could be paid significantly less than a man for doing the same job. Women were thought to be more detail-oriented, their smaller hands better suited for repetitive tasks on the Friden manual adding machines. America’s aeronautical think tank, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (the “NACA”), headquartered at Langley Research Laboratory in Hampton, Virginia, created a pool of female mathematicians who analyzed endless arrays of data from wind tunnel tests of airplane prototypes.

As a child, however, I knew so many African-Americans working in science, math and engineering that I thought that’s just what black folks did.Īfter the start of World War II, Federal agencies and defense contractors across the country coped with a shortage of male number crunchers by hiring women with math skills. There were also black English professors, like my mother, as well as black doctors and dentists, black mechanics, janitors and contractors, black shoe repair owners, wedding planners, real estate agents and undertakers, the occasional black lawyer and a handful of black Mary Kay salespeople. There were mathematicians at our church, sonic boom experts in my mother’s sorority and electrical engineers in my parents’ college alumni associations. Our next door neighbor was a physics professor.

My father’s best friend was an aeronautical engineer. Five of my father’s seven siblings were engineers or technologists.

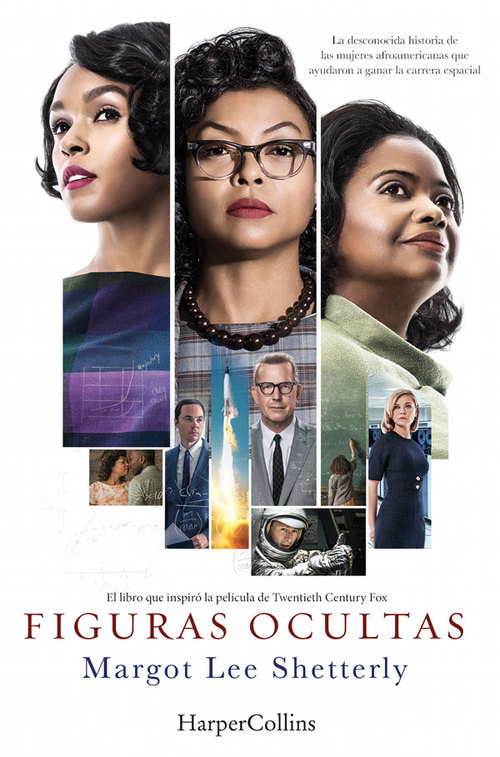

My dad was a NASA lifer, a career Langley Research Center scientist who became an internationally respected climate expert. Just do an image search for the word “scientist”.įor me, growing up in Hampton, Virginia, the face of science was brown like mine. Even Google, our hive mind, confirms the prevailing view. We all know what a scientist looks like: a wild-eyed person in a white lab coat and utilitarian eyeglasses, wearing a pocket protector and holding a test tube. My current work in progress, a narrative non-fiction book entitled HIDDEN FIGURES recovers the history of these pioneering women and situates it in the intersection of the defining movements of the American century: the Cold War, the Space Race, the Civil Rights movement and the quest for gender equality. Most Americans have no idea that from the 1940s through the 1960s, a cadre of African-American women formed part of the country’s space work force, or that this group-mathematical ground troops in the Cold War-helped provide NASA with the raw computing power it needed to dominate the heavens. What about Katherine Johnson, Mary Jackson, Dorothy Vaughan, Kathryn Peddrew, Sue Wilder, Eunice Smith or Barbara Holley? You've heard the names John Glenn, Alan Shepard and Neil Armstrong.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)